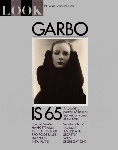

GARBO

IS 65

She has not made a picture since 1941. Yet the world pays instant attention to her ever move. A portrait of the “most enchantingly mysterious woman” of our times.

By JOHN BAINBRIDGE

On the eighteenth of September, Greta Garbo will celebrate, in her fashion, her sixty-fifth birthday. It seems fairly safe to say that she will not meet the press and chat about how it feels to reach three score and five. If she has her way, which she usually does, reporters will not even know where to find her.

She passed her birthday last year in a remote village in the Swiss Alps, where she usually sojourns during the fall. She dined out with a few close friends, drank some champagne, and was home in bed by nine-thirty, as is her custom. She is also an early riser In all ways, except for rather heavy cigarette smoking, she takes very good care of herself. The results are impressive. Today, nearly three decades after her abdication as the first lady of the screen, she is still a stunning international ornament. Inevitably, fine lines have begun to appear around her mouth and around her matchless navy-blue eyes. But the sheen of her hair, the fresh texture of her skin, the litheness of her figure, the vigorous cadence of her walk, the arresting resonance of her voice–all suggest a woman in her early fifties. “She is so beautiful, so beautiful it's incredible,” the novelist Irwin Shaw said after lunching with her recently. That's the way people were talking about Garbo 40 years ago. Her beauty is ageless.

So is her legend. She does nothing to nourish it, except to go on being her elusive self, which seems to be quite enough. Photographers with long-lens cameras continue to lie in wait on the streets, at airports and on Mediterranean beaches in the hope of snapping the face of the century. On the rare occasions when they succeed, the results are published around the world. Any news relating, however remotely, to the world's most glamorous figure in retirement is duly reported in the press. In 1967, the Stockholm apartment house in which Garbo grew up was demolished to make way for a road improvement; American and European newspapers conscientiously informed their readers of this momentous event. During the past few years, there has also been an outpouring of books, articles, and other literary and pictorial efforts attempting to explain the secret of Garbo's enduring appeal. They are interesting but not illuminating. She remains the most enchantingly mysterious woman of her time.

Though Garbo hasn't made a picture since 1941–and almost certainly never will make another–movie producers on three continents have never ceased trying to lure her back on the screen. She has not always turned a deaf ear to their proposals because she had no intention in the beginning of her retirement to make it permanent. Over the years, she has been reported ready to turn to pictures in portrayals of Madame Bovary, Bernhardt, Duse, Modjeska, George Sand and St. Francis of Assisi. In 1949, she actually signed a contract with independent producer Walter Wanger to star in a picture based on Balzac's La Duchesse de Langeais but this project collapsed because of the producer's financial difficulties.

Since then, Garbo has listened to dozens of other film ideas, not a few from producer Sam Spiegel, and read a great many scripts. She has rejected them all–a wise decision in the opinion of James Mason, who was to have played opposite her in La Duchesse de Langeais.

About the Garbo film revival, her comment is brief:

“I don't get a penny out of it.”

“I think she would have to be ever so dotty to make another film,” Mason told a friend in London recently. “Her memory is so gorgeous. Her last picture–that concoction called Two-Faced Woman –may have been unfortunate, appearing in a bathing suit and so on. Nevertheless, there is hardly a foot of her film that is not beautiful, and so it should remain.” Garbo evidently agrees. Nowadays, when anyone suggests that she ought to make another picture, she habitually replies. “What can you do with an old actress?” Her response, though seemingly modest, is oddly misleading, for privately, as everyone who knows her well is aware, Garbo has a very keen sense of her status as the world's most famous living legend. During the past couple of decades, Garbo's fame far from fading, has flourished. The 1960's, is particular, were vintage years for the Garbo legend. It was during that period that she was, in a professional sense, quite miraculously reborn. Through the widespread showing of her films on television and at “Garbo Festivals” both here and abroad, she became a star to a whole new generation–“the generation,” as Vogue put it, “that Never Knew.”

The revival began in the summer of 1963, when the Empire Theatre, in London, put on a five-week season of Garbo films. They set a box-office record for the theatre.

“I've never been so flabbergasted,” the manager told reporters. “At my age–fifty-three–you can't help being a Garbo fan. But three out of four of the customers seeing these films are young people pulled in by curiosity. They come out raving about Garbo.”

The same year, the state-subsidized television network in Italy showed Anna Karenina , Camille and three other Garbo films on five successive Sunday evenings. The films were watched by some ten million people–nearly the maximum Italian television audience. The country's movie houses were suddenly quite empty on Sunday nights, usually their busiest night in the week. The drop in business was so precipitous that the movie exhibitors in Rome closed their theatres for 24 hours in what was called an “anti-Garbo-on-TV” strike.

As the decade moved on, other millions flocked to Garbo festivals from Paris to Los Angeles and at many points between. The most ambitious revival was staged in 1968 by The Museum of Modern Art in New York, which put on for the first time anywhere a complete retrospective of Garbo's film career, beginning with her debut in an advertising short in 1921. Within four days of the announcement of the festival, all of the 12,000 tickets had been sold. Even so, long queues waited outside the auditorium before every performance in hopes that a seat would somehow become available.

It was not only the public that gave the returning Garbo a triumphant welcome. The movie critics–an entirely new generation of them– also celebrated her remarkable resurgence. Like their predecessors in the thirties, the younger critics vied with one another in celebrating Garbo's beauty, especially her face–“the furthest stage to which the human face could progress,” said one British critic, “the nth degree of structural refinement, complexity, mystery, and strength.” It was left to Jack Kroll, in Newsweek , to explain why Garbo still unhinges people this way. “Her genius,” he wrote at the time of the Modern Museum's festival, “was to be all possible objects of desire–innocence, experience, strength, passivity, tenderness, cruelty…. Garbo was something that the male of the species never expected to encounter in this world; but when he did, he realized in his bowels that without possessing this creature he would never be complete.”

If Garbo read Mr. Kroll's rhapsody or any of the other recent paeans, she has never let on. In fact, people who see her frequently have never heard her utter a word about any aspect of the fantastic revival. One friend, unable to restrain himself, did bring up the subject over drinks one afternoon a while ago, saying something about how thrilling it must be once again to the toast of the cinematic world. Garbo's reply was brief. “I don't get a penny out of it,” she said.

When Garbo returned some years ago from a trip to Europe, she was, as usual, asked by reporters about her plans for the future. “I have no plans,” she replied. “I'm sort of drifting.” If her answer was rather melancholy, it was also a remarkably accurate description of the life she has led since giving up her career at the age of 36, when she was at the peak of her powers. She has now spent more then half of her adult years in retirement. “It is almost criminal,” a venerable American actress has said. “She could have been doing such beautiful things all these years.” However much others may lament her aimless and unproductive existence, it seems to be congenial to Garbo, who has always had a strong streak if laziness in her makeup. Furthermore, she has been a very rich woman for a long time. She can afford to do what she wishes, which, as it happens, is very little.

Garbo lives today, as she has for nearly 20 years, in a comfortable but unostentatious seven-room cooperative New York apartment, at 450 East 52nd Street, overlooking the East River. She lives alone, and spends most of her time in solitary pursuits. However, her life is not as reclusive as the legend would have it. (“I never said, ‘I want to be alone,'” Garbo once told a friend. “I only said, ‘I want to be let alone.'”)

Though she may spend three or four days in succession by herself, she has a small circle of New York friends, including Jane Gunther, the widow of the writer; Irene Selznick, the theatrical producer; Charles Addams, the cartoonist; Goddard Leiberson, the composer and CBS executive, and his wife, the former dancer Vera Zorina; Eustace Seligman, the distinguished lawyer, and his wife; and a few other men and woman, most of whom have something to do with the arts or with fashion, and all of whim quality for Garbo's friendship by being devoted, discreet and undemanding.

Of all the friendships that Garbo has made during her retirement, the one that lasted the longest and no doubt meant the most to her was that with George Schlee, a Russian-born entrepreneur who managed the elegant maison de couture of his gifted wife Valentina. Garbo met Schlee in the middle forties, when she was taken Valentina's salon to buy some clothes by Gayelord Hauser, the dashing dietitian and health-food manufacturer who once had the improbable idea of making Garbo his wife. As a consequence of the visit, Valentina and Schlee became good friends with their new customer, and as time passed, Garbo and Schlee became very good friends. A worldly man, intelligent, and with a flair for making money, Schlee was also, in John Gunther's phrase,. “a connoisseur of the art of living.” Furthermore, it developed that Schlee had a talent for giving Garbo directions, a faculty in a man she has always prized.

During the years that followed, Garbo, Schlee and Valentina worked out a design for living that commanded the admiring interest of their mutual friends. In the beginning of his friendship with Garbo, they say, Schlee told his wife, with Continental aplomb, “I love her, but I'm quite sure she won't want to get married. And you and I have so much in common.” Privately, Valentina was said to have considered the arrangement far short of ideal, and, being Russian, to have spoken dramatically of entering a convent. However, thanks to her not inconsiderable talents as an actress, she managed to appear outwardly unruffled.

As the friendship progressed, Garbo bought an apartment in the same building in which Schlee and Valentina made their residence. During the theatrical season, Schlee sometimes appeared at an opening one night with Garbo and at another the following night with Valentina. The trio occasionally spent weekends together at the homes of friends, though more often Garbo and Schlee arrived by themselves. Once, when Schlee was in the hospital, Garbo and Valentina spelled each other in providing him company; Garbo handled the afternoon visit, while Valentina was tending to her work, and she took the evening assignment. Valentina continued to make many of Garbo's clothes. On one occasion, the two women, escorted by Schlee, arrived at a dinner party wearing identical costumes that Valentina had designed. Since she bears a noticeable physical resemblance to Garbo and since the two in this occasion had combed their hair severely back from their foreheads and were even wearing the same kind of makeup, their appearance, and all things considered, made a lasting impression on the other guests.

As a rule, Garbo and Schlee spent most of the summer at Cap-d'Ail, on the Riviera, living in a villa aptly named “Le Roc.” Bleakly situated at the tip of a peninsula of sheer rock, the square-shaped building looked quite unattractive from the outside, but Valentina had decorated the interior with great charm and style. Though the villa was generally referred to in the neighbourhood as “Garbo's house,” it had been bought and was owned by Schlee. Garbo and Schlee kept to themselves, pointedly avoiding their neighbors, and never, as far as they happened to notice, entertaining any guests. Residents nearby were aware that Garbo usually took an early morning swim, after a maid had reconnoitered the area to make sure that it was clear of photographers. Doffing a white terry-cloth robe, Garbo, clad only in rather long swimming trunks, would plunge into the water. She also preferred to be topless when sunning near the villa:

Besides idling about Le Roc, Garbo and Schlee often went cruising on yachts belonging to various friends, including Aristotle Onassis, Ricardo Sicre, a Spanish-born American financier, and Sam Spiegel, the movie producer. (In the late fifties, Winston Churchill was also frequently among the other guests on the Onassis yacht.) “Schlee was like a manager,” one of the seafaring hosts has recalled. “He had absolute control. When he didn't want to do something, they didn't do it, no matter how she felt about it. On the boat, she was always very pleasant, very gay, very amusing. She didn't talk a great deal. You might have thought that she was in the clouds, not really listening, and then she would make some comment that would show she had been following it all right along. She liked very much to get compliments from men. This made Schlee very upset. He was as jealous as the devil. I don't think he could tolerate having her exposed to other people, especially to interesting or attractive men. Whenever that happened–and it happened several times–he would invent some excuse for cutting the trip short. He'd say he had forgotten about having to get back to meet a lawyer or a banker from New York, or something of the sort. So we would put into a port, and they would hire a car to take them back to their place. She never objected, never said a contrary word. Schlee dominated her completely.”

Although she seems to be in excellent health,

a friend calls her “wildly hypochondriacal.”

During the first week of October, 1964, Garbo and Schlee arrived in Paris from the Riviera and checked into adjoining rooms at the Crillon Hotel. The following day, Schlee, who had not been in good health for a couple of years, died suddenly of a heart attack. “I'm afraid Garbo didn't cope very well,” a woman who was close to the situation has since remarked. “She packed her bags and fled to a friend's place.” Valentina, escorted by a pair of New York bachelors, flew to Paris to claim her husband's body and accompany it back to New York. She let it be known that Garbo would not be welcome on the same plane or at the funeral. “Valentina doesn't feel she has to put on a show any longer,” a friend has said. “First, she rid the villa of photographs and mementos and all other relics of Garbo. Then she put the place up for sale. Not only that. She called in a Greek Orthodox priest to exorcise Garbo's presence from her–Valentina's–New York apartment. I understand the exorcising was very thorough, including even the refrigerator. Apparently Garbo was in the habit of looking in there for snacks.”

Though Valentina and Garbo continue to live in the same apartment building, they both now take elaborate precautions to avoid meeting in the lobby or in the elevator.

Garbo was deeply affected by Schlee's death, so much so that she was, as one of her friends put it, “in deep mourning.” The depth of her grief surprised some people who had known her for a great many years. It was the first time they had seen her weep. “If she loved him, she didn't realize it until afterward,” one of her old but less reverent friends has said. “My personal opinion is that she isn't capable of love. What she probably missed was the companionship and sense of protection he provided. She has always needed a sort of Big Daddy in the background.”

Left without her special friend and protector, Garbo has taken up with some of her companions of earlier years, including Gayelord Hauser. Thanks, apparently, to his continued intake of blackstrap molasses, yoghurt and other “living” foods, Hauser, at 75, still a bachelor, remains full of bounce, and is noticeably pleased to resume the role of occasional escort. Garbo spent part of the summer following Schlee's death cruising among the Greek islands with two other old friends, Cecil Beaton, the fashionable British photographer and man about the arts, and Baroness Cecile de Rothschild, on the latter's yacht. The Baroness, a daughter of a French banker,, is a white-haired, self-assured, cosmopolitan woman, who has made a reputation as connoisseur of objets d'art and people. Being the kind of person who is accustomed to taking command, she was the one to whom Garbo turned when Schlee was stricken, and it was to her Paris residence that Garbo repaired.

The Baroness is among the select few who visit Garbo in her apartment and are entrusted with her private telephone number. Possession of the number does not, however, guarantee getting through to its owner. As often as not, Garbo will answer the phone, and even if the caller's voice is as instantly recognizable as, for example, Cecil Beaton's, she will reply in the impersonal tone of a maid, “Miss Garbo isn't in. Is there a message?” Not all of her friends find this little conceit amusing.

In the past few years, Garbo has also resumed her friendship with Salka Viertel, the Polish-born actress and writer, who was probably Garbo's closest confidante and adviser during her years in Hollywood. Mrs. Viertel now lives in Klosters, the famous ski resort in Switzerland, where her son, Peter, a writer, and his wife, Deborah Kerr, and their family also make their residence.

Garbo now customarily spends several weeks in Klosters during the fall. At that season, the village is virtually deserted of visitors; she can accordingly move about freely without attracting attention, and thus probably behave more naturally than she can anywhere else. But what really attracts Garbo to Klosters is, of course, the presence of Mrs. Viertel. Now in her early eighties, small, white-haired and elegant, she remains a woman of great charm, dignity and generosity. “For Garbo, Salka is like a nanny,” a friends who sees them often in Klosters has said. “She looks after her. In a way, it's like a daughter coming home.”

When Garbo first started sojourning in Klosters, Mrs. Viertel, who lives very modestly in a small chalet, arranged for Garbo to use the apartment belonging to Anatole Litvak, the movie director. He later sold his place to Gore Vidal, the novelist, and since he, like Garbo, also enjoys being in Klosters in the fall, Mrs. Viertel was obliged to find other quarters for her. She called several friends who have apartments or chalets in the village, and asked if Garbo “could have” one of them for a few weeks. The matter of rent wasn't mentioned. At length, Mrs. Viertel arranged for Garbo to occupy the apartment owned by Comte Frederic Chandon de Briailles, familiarly known as Freddy, who is vice president of the Moët & Chandon champagne firm and a friend of Peter Viertel. The apartment of “F. Chandon,” as the nameplate reads, is one of four in a two-story chalet that is about a ten-minute walk from the center of the village. The building looks toward the public tennis courts, where Garbo accasionally plays tennis with one of Mrs. Viertel's granddaughters.

In addition to finding pleasant living quarters on ideal terms, Mrs Viertel also provides Garbo with the kind of social setting that she finds agreeable, one that is interesting, circumspect and untaxing. She has the chance to meet all kinds of people–writers, artists, musicians–who come to visit rs. Viertel as well as her and the Peter Viertels' friends who maintain residences in Klosters, among them, Gore Vidal, Robert Parrish, the film director, and his wife, and Irwing Shaw. Garbo appears to be at ease with all of them, especially with Shaw. “Irwing has a very good way with her,” one of the Klosters group has said. “He's jolly and a little bit flirty, and she likes that.” Shaw occasionally takes Garbo and Mrs. Viertel to lunch at the Chesa Grischuna, the most fashionable hotel in Klosters, and Garbo has also often been among the dinner guests at his chalet. “One night when she was leaving, I kidded her,” Shaw has recalled. “I said, ‘Look, Greta, I've entertained you umpteen times at my house. Now it's time for you to entertain me.' You know what? She did. She gave a dinner party for twelve of us at the Chesa. She was so conscientious that she arrived there at six o'clock and hovered about to make sure everything was exactly right.”

Normally, Garbo's life in Klosters is as uneventful as it usually is anywhere else. She rises early and eats a light breakfast. She whiles away the early morning reading newspapers, and about ten-thirty sets off for her daily walk into town.

As she strode toward the village one crisp morning not long ago, she was wearing rather large dark glasses, a black pea jacket, a white turtleneck sweater, beige slacks and soft-soled shoes. Over her shoulder, she carried a brown-leather bag. Her light-brown hair, worn slightly less than shoulder length, was combed back and held by a black ribbon. Smaller in stature and thinner in the face than on remembers her from the films, she looked as chic as ever.

Reaching the main street, she stopped to look in the window of a boutique called Zimba, and then went inside. She looked at sweaters and scarves. Speaking in a very soft and pleasant voice, she asked the clerk to see some woollen stockings. She bought one pair. As a rule, she doesn't act with such haste in making a purchase. When, the year before, she decided to buy a parka, Mrs. Viertel went with her to every clothes shop in town, not once but several times, before Garbo finally made up her mind. Back on the street, she looked in the windows of a couple of other shops, and then stopped in the Spiess butcher shop, as in her daily custom, and bought one small steak.

A half-block away, she entered a tobacconist-newspaper shop, bought a couple of newspapers, and thanked the proprietress. (Garbo is unfailingly courteous to clerks, servants and others in similar positions.) Outside again, she headed toward home, passing the Cinema Rex, which she has never been known to attend, and onto a walk through an open field where beginners' ski classes are held in winter. Her day's work was finished.

Though Garbo is occasionally invited out to lunch, she normally takes it at home alone, eating her steak. She relaxes for a while, and then goes for a walk, always alone, on one of the mountain paths. On the afternoon walks, she strides even more vigorously than she does on the morning outings. Like an athlete, she often carries an extra sweater or two, putting them on and taking them off when she moves from the shade to the sun and back again. She prefers to lower and safer, if less scenic, paths; this is sensible, since the purpose of her walk is not sight-seeing but exercise, which she considers a daily must. As far as anybody knows, the only time she has suffered any serious physical ailment was in 1962, when, for a period of time, she had twice-weekly treatments for arthritis at New York University's Medical Center. Though she now seems to be in excellent health, she is, as one of her friends has said, “wildly hypochondriacal,” and never tires of discussing her ailments, real or imagined, often with childish frankness.

After her walk in the mountains, Garbo takes a short nap, and in the late afternoon goes to Mrs. Viertel's chalet for tea. This is the high spot of Garbo's day. There are usually other guests, often film or literary friends of Mrs. Viertel. If they are strangers to Garbo, she doesn't seem to enjoy herself as much as she does when only Mrs. Viertel and some of her local women friends are present. On these days, Garbo is relaxed and quite talkative. “It's just sort of girl talk,” one of the guests has said. “There's a little giggling and chatter. One day, she said that on her walk in the mountains, a man had chased her or waved at her with a cane. It wasn't quite clear what had happened, but she made quite a production out of it. ‘Oh, it's ruined everything,” she said, looking very sad. Another time, she told us that on her walk, she had met a woman with a moustache. She said, ‘She was one of the most beautiful woman I have ever seen.' We didn't know whether this was supposed to be a joke, or what. Nobody laughed.”

“Greta would make a secret out of whether

she had an egg for breakfast.”

Garbo doesn't usually enliven the teas with such interesting contributions. Her conversation is normally concerned with less exciting matters, such as her plans to buy a new sweater, her satisfaction with a new pair of walking shoes, or where she plans to hike the following day. “She talks only about herself, but she doesn't talk about herself at all,” one of her tea companions has said. “In other words, she talks almost exclusively about things that relate to herself, but only in an impersonal way–her walks, her shopping plans, and so forth–but never a word about her thoughts or ideas or hopes or plans or anything else that would be self-revealing in any way.”

Garbo's day usually ends when the tea ends, though she may once in a while attend a small party, such as the champagne-and-caviar do that Gore Vidal laid on after buying his Klosters residence. Since champagner and caviar happen to be two of Garbo's favourites, she didn't stint herself on the refreshments. Becoming very merry, she laughed and made little jokes in her rather heavy-handed way. “She was much struck by Gore,” giggles and flirting like a schoolgirl.” She invited Vidal to sit by her near a front window, and talked about the days when she lived in the same apartment. “This is where I used to curl up every night and have a whiskey and watch the people of Klosters,” she said, casually striking a pose as memorable as something from one of her films. That the scene from the window embraced nothing more memorable than a grocery store and a tobacco shop only added to the poignancy of the line. Though obviously enjoying herself, Garbo left the party shortly after nine, and walked home alone in the late twilight. She one puzzled a friend in Klosters by remarking that she didn't know where any of the light switches were located in Chandon's apartment. It was one of her typically offhand remarks that don't require a reply, but it stuck in her friend's mind. She subsequently concluded that the reason Garbo didn't know the location of the switches was that she was always in bed before it was dark, and so had no need for artificial light.

“I suppose it's some kind of index to the life she leads,” the friends said.

When the skiing season approaches and Klosters begins to fill with people, Garbo returns to New York, and melts into what she considers its agreeable anonymity. She spends a great deal of time in her apartment (“I had a hard time getting this apartment,” she once told a friend. “They don't like actresses in this building”), which is furnished in good but undistinctive taste. The living room has an attractive air, owing in part to its several valuable paintings, including a Renoir and a Modigliani; the other rooms have a rather spare, institutional look–“Swedish Impersonal,” as one visitor has described their décor. Garbo doesn't like having servants around, and gets along with the services of a cleaning woman, who comes in twice a week. On the rare, though in recent years slightly more frequent, occasions when Garbo invites one or more of her friends for drinks or what passes for a meal (usually something from a delicatessen), she manages the uncomplicated hostess task herself. The fact that it's cheaper that way is only an incidental consideration, but still a consideration. Though she is several times a millionaires, she is disinclined to spend money unnecessarily, except occasionally on herself. Once, after she had purchased a pair of very expensive sweaters at Sulka, she remarked to her shopping companion, “And I am supposed to be so mean.”

What seems to be Garbo's reluctance to give money, either publicly or privately, or time, of which she has an abundance, continues to be a source of nagging concern to some of her less retentive friends. “My God!” one of them exclaimed when the subject came up recently. “Doesn't she ever think of anybody but herself?” However, most of Garbo's friends have long since learned to accept her for what she is and always has been–a woman with a child's charming innocence. She is shrewd, selfish, willfiul, superstitious, instinctive, suspicious, completely self-absorbed. She is secretive (“Greta would make a secret out of whether she had an egg for breakfast,” a friend has said), and she has a childlike indifference to all desires but her own. One of the reasons that she has always lived in a small, cloistered world springs from her inability to accept the responsibilities of adult friendship.

A woman who has known Garbo for many years in both Hollywood and New York has said, “Greta is like the Mona Lisa–one of the great things in life. And as unattached to you as that.”

Garbo was once asked by a European friend how she spends her time in New York. “Oh,” she replied, “sometimes I put on my coat at ten in the morning and go out and follow people. I just go where they're going. I mill around.”

She is often seen these days milling around on Fifth Avenue or Third or Madison or on the side streets uptown. Mostly she window shops. Almost anything, from the goods in the window of a jewelry store to a booklet on inflation in a bank window, will momentarily engage her attention. From time to time she makes a purchase, often something at a health-food store, or performs an errand. “The high point of her day would be to got to Saks or Bonwit's to exchange a sweater,” a friends has said. “Then she would go home and take a nap.”

On her random walks about the city, Garbo customarily wears conventional street clothes–a dress, a coat or jacket, a modified face-concealing hat (or in warm weather, a kerchief), low-heeled shoes and plain dark glasses–that are intended to make her unobtrusive. To certain extent they do, because the world has now caught up with the casual style that has been hers since the thirties. Trousers, turtleneck sweaters, dark glasses, see-through blouses–she was wearing them all decades ago. Despite her intentionally plain everyday clothes, there is something about Garbo's ambiance that causes her to be recognized (though seldom accosted) by passersby. They react to the experience in different ways. Jack Pollock, the noted abstract painter, was walking with friends on Third Avenue one spring afternoon when Garbo strode past. Without a word, Pollock abruptly turned around and followed her; his friends didn't see him again that day. The responses to a Garbo encounter are generally less dramatic, usually ranging from a look of wide-eyed surprise to an audible gasp and perhaps the whispering of her name. However the shock of recognition manifests itself, Garbo pretends not to notice, and goes on her silent way.

Garbo's days are not always spent alone. She may lunch at The Colony with Jane Gunter or have a healthful snack with Gayelord Hauser or go to some small, fashionable restaurants with the Baroness Rothschild, if she happens to be in town. Once in a while in the afternoon, she may stop by the apartment of one of her woman friends who live in New York. She almost never calls ahead of time (she has always been reluctant to make an appointment much more than an hour in advance), and she departs as abruptly as she arrives. A retired professional woman upon whom Garbo calls every once, in a while has described her visits by saying, “It's like being friends with a hummingbird. She lights on your hand, and there is this vivid creature, and then she flies away.”

Garbo appears on the New York social scene much less frequently now than she did when Schlee was her escort. In those days, she was seen at enough parties to acquire the reputation of being what a local wit called “a hermit about town.”

Many of her evenings are now spent at home alone watching television. However, she still goes out for drinks or dinner at the homes of old friends, and usually appears to be enjoying herself. Most of the other guests at such functions she has met before; also, being mainly people of affairs or celebrities themselves, they are not likely to pay her so much attention as to make her uncomfortable. There seems, in fact, to be a spontaneous conspiracy to pretend that she is just another guest; a considerate idea, but not easily realized.

“It is about as easy to relax in her presence as it is with royalty,” a man who sees her often socially has said. “That is too bad, because she can be very human. The trouble is that she isn't allowed to be, at least in our own minds.”

An anomaly of Garbo's private life and her profession is that she was able to express emotions with such liberated clarity on the screen, and yet away from it, self-expression has always seemed a rather difficult process. With an individual person or with a couple of friends, she can carry on a conversations, especially on an uncomplicated subject like travel, without the noticeable discomfiture that once bothered her; in fact, when she cares to, she can be very good company indeed. She participates very little in general conversation among a number of people. The few remarks she makes in these circumstances are confined as a rule to brief side comments on the subject being discussed. She shies away completely from any discussion of movies, old or new, and she never refers in any way to her own career. “It's as if it never happened,” a friend has said. She is better at listening than talking; she enjoys hearing gossip (she is not at all given to saying a malicious thing herself); and she laughs appreciatively at jokes of a fairly elementary nature. Her private sense of humor is not excessively refined; she can be amused by a rather exhausting story about a centipede taking off its shoes.

It has long been Garbo's peculiar burden that because of her legendary quality and her Sphinx-like air of omniscience, people expect that she is constantly at the point of saying something of vast import. The few Garbo utterances that have made a lasting impression on her friends are notable less for impression on her friends are notable less for profundity than mysteriousness. A traveling companion once found her sitting on the floor in blankets. Asked what she was doing, Garbo solemnly replied, “I am an unborn child.” Another time, she surprised a friend by saying, “I had an awful row with God this morning,” a remark the more bewildering because Garbo is not known to have strong religious inclinations. Politics, ideologies, the state of the world interest her hardly at all. (She became an American citizen in 1951 – “I am glad to become a citizen of the United States,” was all she had to say on that occasion–but she seems never to have voted.) Nor have intellectual or literary pastimes claimed her attention. Friends have giver her books and been disappointed never to learn whether she has opened them. She apparently thinks little about anything except what applies to her own life immediately and directly.

Perhaps none of Garbo's more common idiosyncracies tries the patience of her friends more often than her habit of vacillating about accepting social invitations of any kind. When she receives an invitation, she may accept at once, call up later and decline, change her mind again and perhaps even one again and, finally, appear or not, depending apparently on her mood at the last minute. “She can drive you straight up the wall, “ a New York hostess with much Garbo experience has said. “But once she arrives, you know it's been worth all the agony. She always looks stunning, and when she wishes, she really puts herself out to be pleasant and agreeable.” one of the people for whom Garbo put herself out much more than usual was Jacqueline Kennedy, whom she met at a dinner party before Mrs. Kennedy's marriage to Onassis. Though Garbo has never expressed any interest in politics, she did respond to the Kennedy charisma. “She seemed to have very affectionate feelings toward both Jack and Jackie,” a friend has said. “I think she admired them in the way she would admire highly professional theatrical people.” At the dinner party, Garbo was at her most amiable and charming, and the two women seemed to get along very well. Rather early in the evening, Garbo rose and said, jokingly, to the hostess. “I must go. I am getting intoxicated.” After she had lest, Mrs. Kennedy, who obviously was not attuned to Garbo's rather simple notion of humor, said, “I think she was.”

Though Garbo is not prudish, she is visibly offended by coarse language. At a dinner party not long ago, she sat opposite a famous author who had drunk well but not wisely and whose conversation had become rather gamy. Garbo turned him of by ceasing to pay him any attention, pretending, in effect, that he didn't exist.

She is very much aware that she is a priceless addition to any social gathering, and has long since become accustomed to being recognized instantly by everyone present. She is genuinely surprised if, as happened at a party in New York a couple of years ago, someone doesn't. “You know,” she said to the hostess afterward, “that man didn't even know who I was.” Nowadays, Garbo usually arrives at parties alone and leaves alone. “Many times I have asked if I could take her home,” a man who frequently attends the same affairs has said. “She always says, ‘Oh, thank you so much. I can manage.' You often wonder how she does get home.”

That isn't the only thing that people who have known Garbo for a long time still wonder about. One recent afternoon, she was having a drink with a friend on the terrace of his New York apartment and chatting, as usual, about small, impersonal matters. There came a gap in the conversation. The silence was broken when Garbo, apropos of nothing that had been touched upon before, said, “I am a lonely man circling the earth.”

Her host, a man of notable directness, said, “What do you men by that?”

Garbo took a sip of her vodka. “Someday,” she said, “I will tell you….” She smiled briefly, and the subject changed.

None of Garbo's friends would think of urging her to explain the teasing, arcane remarks that she occasionally makes any more readily than they would consider inquiring about her habit of referring to herself in the masculine gender. “You know,” Garbo is apt to say, excusing her early departure from a party, “he's got to be in bed by nine-thirty.” Speaking of smoking, she sometimes says, “I have been smoking since I was a small boy.” She seems amused at times by the effect of quips like these on people she is with. “She says something like that and then sort of laughs,” one of her New York escorts has said.

What George Cukor, who was probably Garbo's favorite director, recently called, “Garbo's own brand of eroticism” came through to the younger generation of critics. Penelope Gilliatt, reflecting on the matter, wrote: “She always seems miles beyond the boundaries of sex, equally and pityingly remote from the men who are in love with her and the women who are vying with her…. She droops like a girl, strides like a man, has the concave chest of an English public schoolboy, and carries her beautiful shoulders as though they were a yoke of milk pails. She looks ravishing in Camille's balldresses and heroic in long boots, but only really moderately at home in any clothes at all.” In spite of a few small revelations from time to time, Garbo's inner life remains as essentially private at 65 as it was at 25. To this day, it is doubtful that anybody really understands how Garbo's mind works or what she thinks about fundamental matters, if indeed she thinks about them at all. “She has the native intelligence typical of a peasant,” Marlene Dietrich once observed, in what may not rank as the most dispassionate judgment ever made. Like so many great actresses, Garbo may never have possessed a particle of intellectual power, but she had genius before the camera because she was guided by a secret, sublime, infallible instinct to do the right thing in the right way. So unerring was her instinct that it produced the illusion of a most subtle intelligence. The magic is still there in real life, too, though it may not always be instantly apparent. “She never does anything that's bad or unruly or very interesting,” one of her oldest New York friends said recently. “You might think she was more like a well-trained child. But then you see her, and you realize all over again that there's just nothing on earth like her.”

Ultimately; of course, how Garbo stands in the opinion of her friends, what she thinks, how she spends her days and nights–such matters are of no importance. What matters is her uniqueness as an actress. Her legacy is the artistry preserved in her films, and they, as recent events have amply proved, will endure. “She is the true immortal,” David Robinson, one of the perceptive younger critics, wrote last year. “Other legends and other goddesses crumble and fade into lovable or laughable antiques; but Garbo miraculously remains.”

END

Copyright © 1970 BY JOHN BAINGRIDGE ADAPTET FROM “GARBO,”

TO BE PUBLISHED BY HOLT; RINEHART & WINSTON, INC. |